And still, jólabókaflóð continues.

As it has been for the past few years, my general reading plan was to select more volumes from my shelves (i.e., books purchased in 2022 or earlier) – specifically, at least twenty-four non-fiction titles and at least one book from each of the special collections in my home library: Shakespeare (about or retold), poetry, NYRB, Kurt Vonnegut (by or about), Joyce Carol Oates (by or about), philosophy, art, and children’s / YA. Although more than half of the books I have read this year were from the shelves, only twelve of the thirty-five non-fiction works were, and I fared only a bit better with the special collections, missing on both NYRB and art:

■ Of Human Kindness: What Shakespeare Teaches Us About Empathy (Paula Marantz Cohen; 2021)

■ Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World (Pádraig Ó Tuama; 2022)

■ And So It Goes: Kurt Vonnegut: A Life (Charles J. Shields; 2011)

■ Babysitter (Joyce Carol Oates; 2022)

■ The Republic (Plato; 375 BCE)

■ The Lemming Condition (Alan Arkin; 1976)

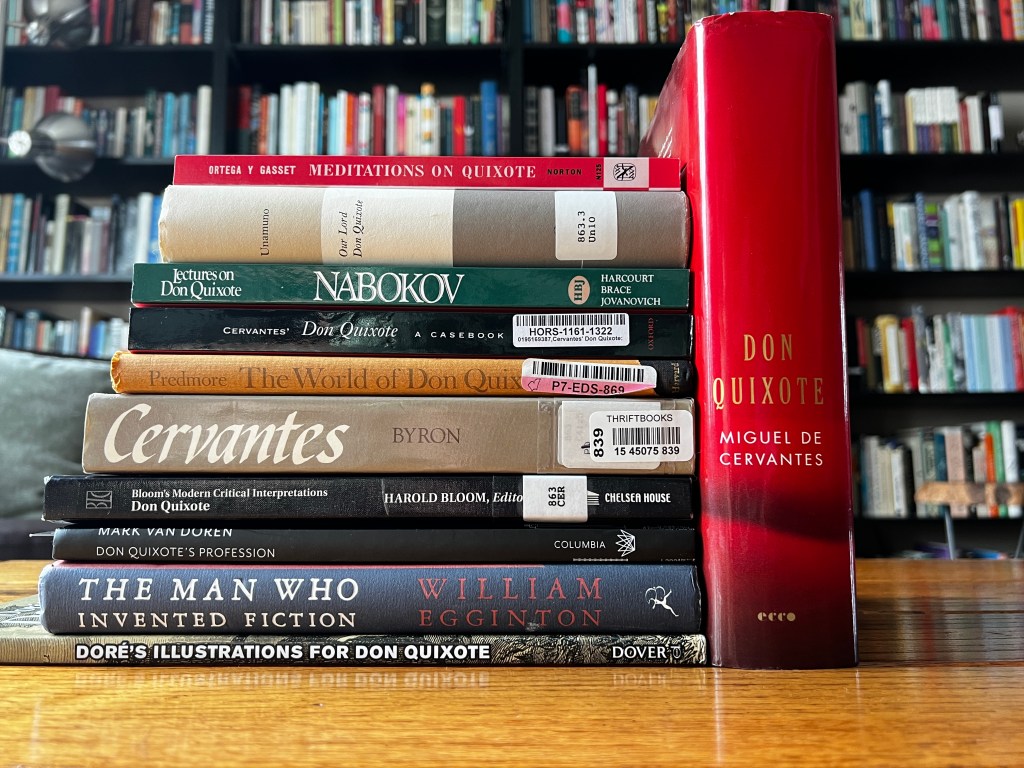

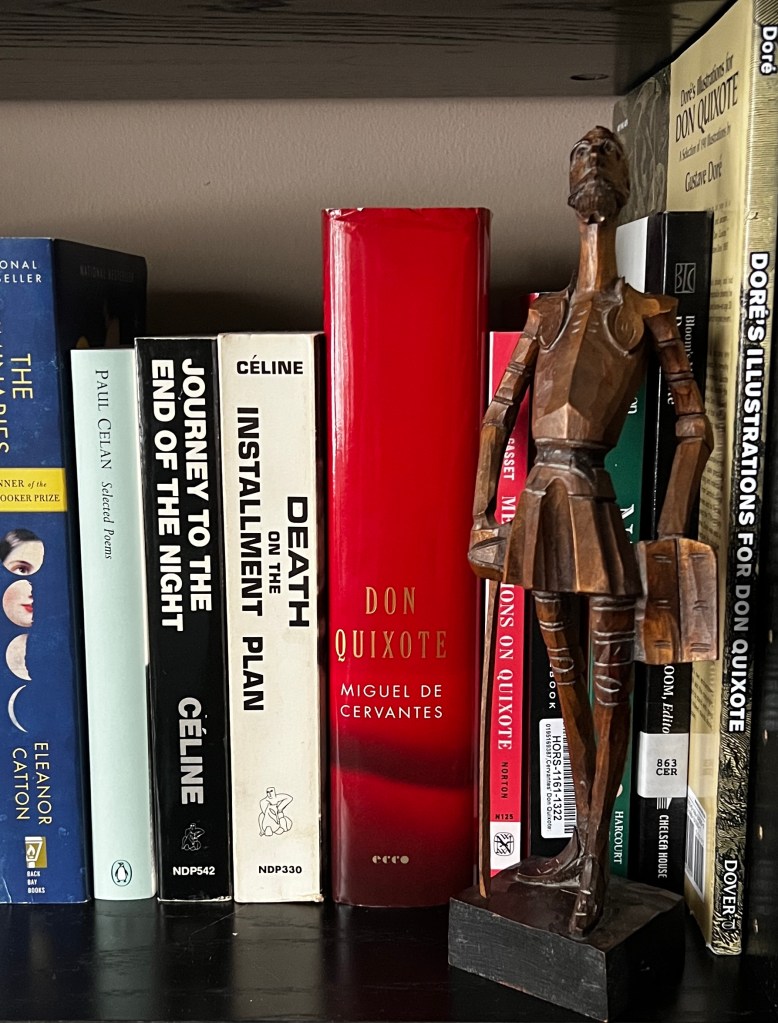

It was certainly a wonderful year of reading, though. With the Catherine Project, I read and studied Don Quixote (Miguel de Cervantes) in a tutorial and The Republic (Plato) in a small reading group led by a professor of philosophy. In a course at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, I finally read the Emily Watson translation of The Odyssey (and I still prefer the Fagles). I reread Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (Herman Melville; 1851) with both Night School Bar and the University of Chicago Graham School. With the latter, I also (finally!) read The Moonstone (Wilkie Collins; 1868). (Soon after that course, a classmate and I did a “buddy read” of The Woman in White (1859) and decided that The Moonstone is the better book; in fact, it was one of my favorite books of the year.) With A Public Space’s APS Together, I read Michael F. Moore’s new translation of The Betrothed (Alessandro Manzoni; 1827), The Haunting of Hill House (Shirley Jackson; 1959), and New Grub Street (George Gissing; 1891). (The Gissing, which had been on my shelves for more than thirty years, was so compelling, I soon followed up with The Odd Women (1893).)

Here are a few of the other groups with which I read:

Premise Institute

■ Hello, Stranger: How We Find Connection in a Disconnected World (Will Buckingham; 2021)

Cardiff BookTalk

■ Watership Down (Richard Adams; 1972)

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

■ Necessary Trouble (Drew Gilpin Faust; 2023)

The Deep Read: The Humanities Institute at University of California Santa Cruz

■ Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future (Elizabeth Kolbert; 2021)

Faulkner in August

■ Absalom, Absalom! (William Faulkner; 1936)

Victober

■ Wuthering Heights (Emily Brontë; 1847)

■ The Way We Live Now (Anthony Trollope; 1875)

In addition to reading and studying, these courses, programs, and groups offer opportunities to meet and connect with other readers, and with several who decided to continue meeting after the conclusion of a 2022 group, I finally tackled Crime and Punishment (Fyodor Dostoevsky; 1866). In April, I led a meeting on The Emigrants (W.G. Sebald; 1992/1996) for a few of those readers, and one invited me to an altogether different spinoff group to read Far from the Madding Crowd (Thomas Hardy; 1874). That same reader and I have continued reading, corresponding, and meeting. Our first “duet” project was Nights of Plague (Orhan Pamuk; 2021). That went so well, we decided to embark on a slow read of The Magic Mountain (Thomas Mann; 1924), which we will finish in March. Our shared love of quality children’s literature and our work as writers and editors led to deep dive into the work of E.B. White, including Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, and The Trumpet of the Swan. We will discuss the first ten or so pieces in Essays of E.B. White next week, and once we’ve finished discussing White and Mann in early 2024, we plan to read Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels.

Great stuff, right?

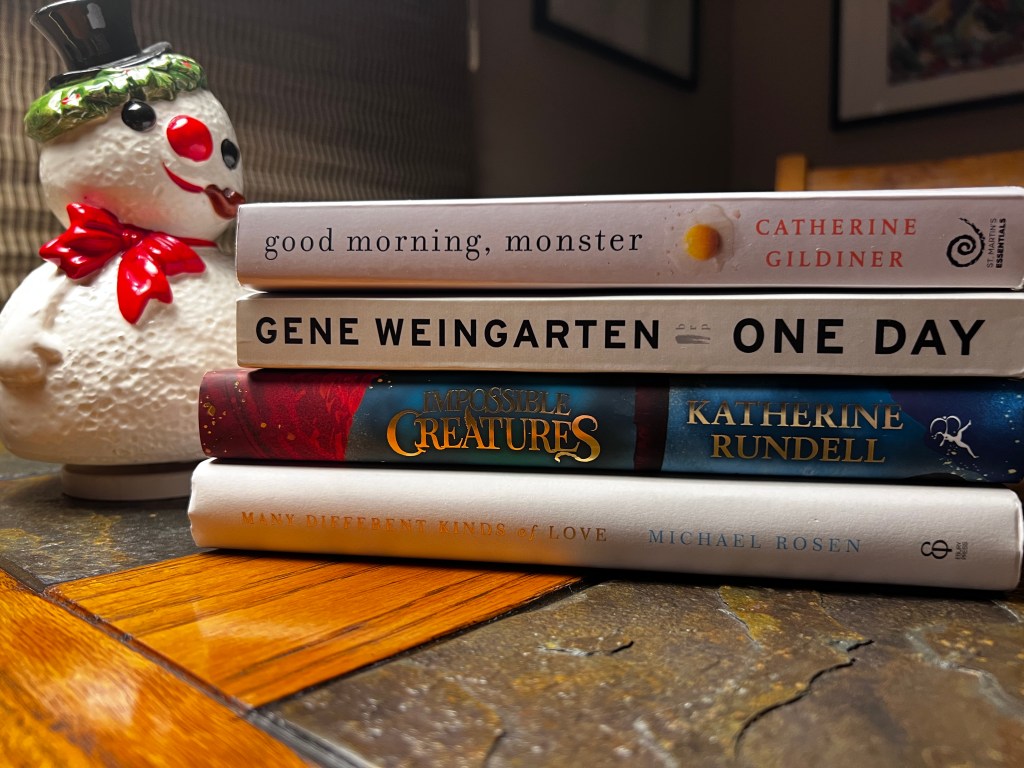

Speaking of great, of the one hundred and twenty-two of books I have read so far, eighteen were published this year, and the standouts were I Have Some Questions for You (Rebecca Makkai), The Last Devil to Die (Richard Osman), To Name the Bigger Lie (Sarah Viren), and Chain Gang All-Stars (Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah). Honorable mention goes to What You Are Looking for Is in the Library (Michiko Aoyama), a book that could have been twee but was quite lovely and life-affirming. Obviously, I appreciate the occasional “feel good” book in my stack. How else would I explain my immediate and deep affection for Osman’s Thursday Murder Club series, of which The Last Devil to Die is the fourth title?

As I mentioned above, The Moonstone was one of my favorite books of the year. Others include Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution (R.F. Kuang; 2022), Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World (Pádraig Ó Tuama; 2022), New Grub Street (George Gissing; 1891), Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty (Patrick Radden Keefe; 2021), and, of course, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (Herman Melville; 1851).

Some(what random) statistics:

— 7 dramas, 3 of which were by Shakespeare

— 5 works of poetry

— 20 graphic works, 7 of which were non-fiction

— 34 library books

— 24 rereads