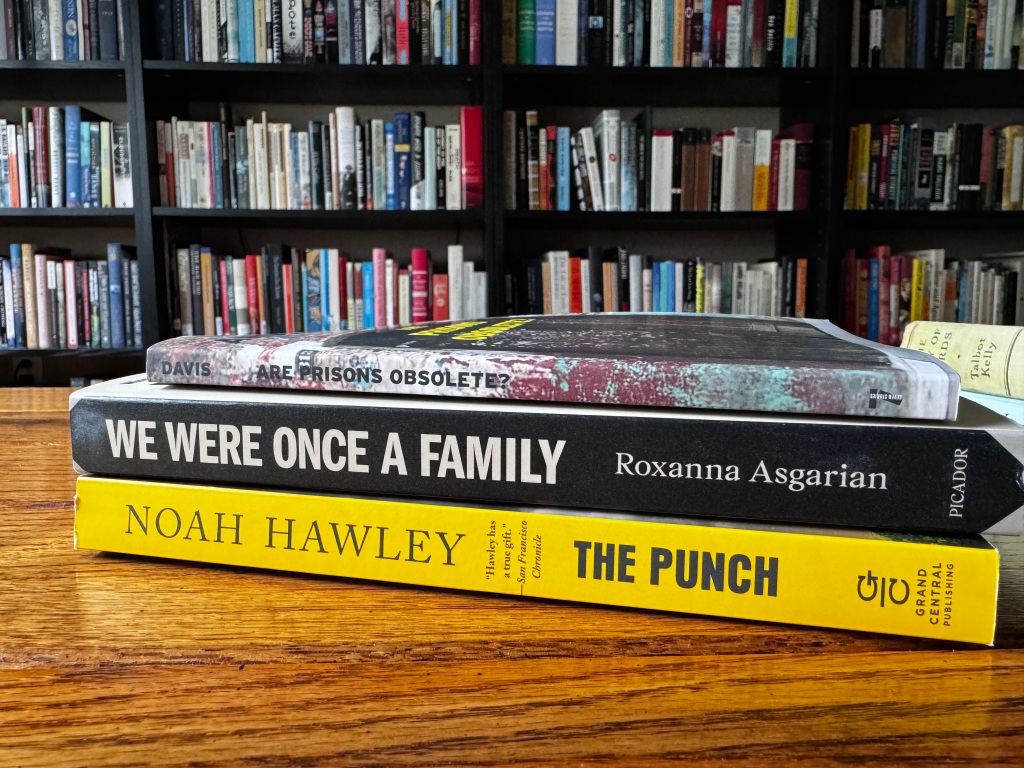

The books pictured above were part of last weekend’s haul from two favorite independent bookstores: Literati and the Dawn Treader, but it will be a while before I get to them. This morning I will finish Hernan Diaz’s Trust for UCSC’s The Deep Read and likely turn to Elena Ferrante’s The Story of a New Name for an ongoing reading project with a friend.

Here are the books I read in April:

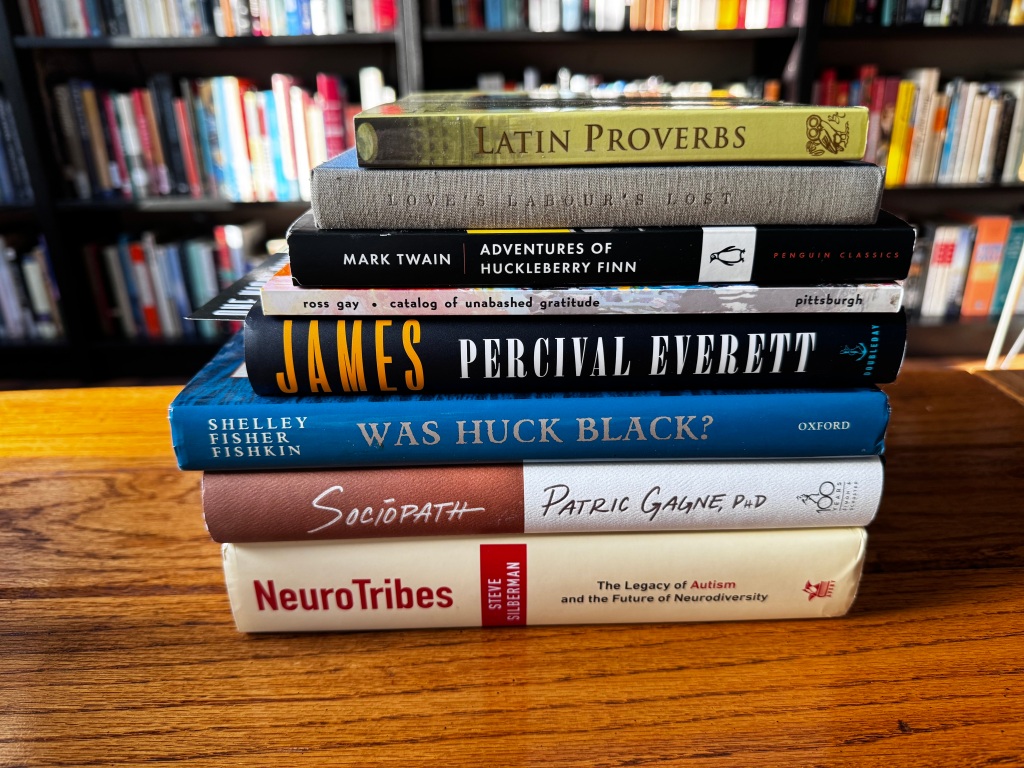

■ Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Mark Twain; 1885)

■ James (Percival Everett; 2024)

In March, John Warner of Biblioracle wrote, “I almost cannot imagine a future where teachers assign ‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ without also assigning ‘James’ alongside it. Doing such a thing would be an amazing opportunity for discussion and learning for students of any age.” Agreed. Last month, I reread Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for a Newberry Library course. At the first meeting, participants agreed to add James to the syllabus, and at our final meeting, with only one exception, we agreed that the discussion and experience were richer for having read both novels.

■ Love’s Labor’s Lost

■ Romeo and Juliet

April and now May have been much busier and more random than I prefer, so while I have not abandoned my third Shakespeare in a Year project, I have definitely fallen behind.

■ My Ántonia (Willa Cather; 1918)

I have not, however, fallen behind on my Cather project (i.e., read her twelve novels in publication order, one per month). It has been about thirty-five years since I first encountered My Ántonia, so when I sat down with it last month, I remembered little more than how much I admired Cather’s style. Well. My younger self had good reading taste if poor retention: This book is perfect.

■ Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (Tom Stoppard; 1966)

Reread in anticipation of the well-reviewed Court production. (Review here.)

■ The Lifted Veil (George Eliot)

A friend hosted a small group to discuss this slim work — an atmospheric novella with a wildly unreliable narrator that shares more characteristics with Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde than with any of Eliot’s own novels.

■ Sociopath: A Memoir (Patric Gagne)

■ This American Ex-Wife: How I Ended My Marriage and Started My Life (Lyz Lenz)

Both of these non-fiction titles were published this year, and both interested me enough to read now rather than later. Reviews here and here.